|

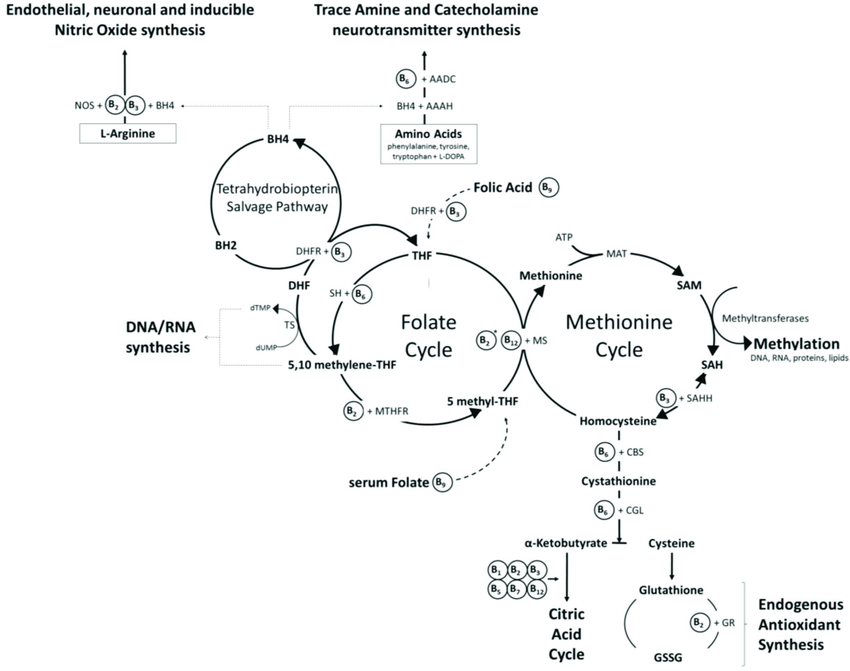

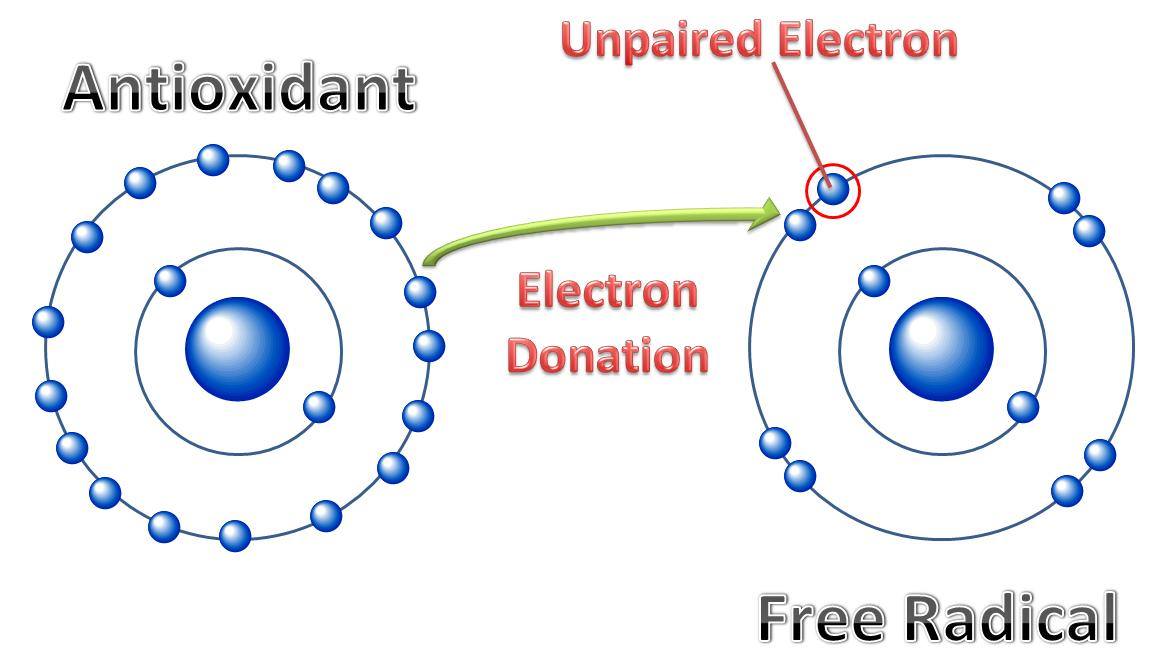

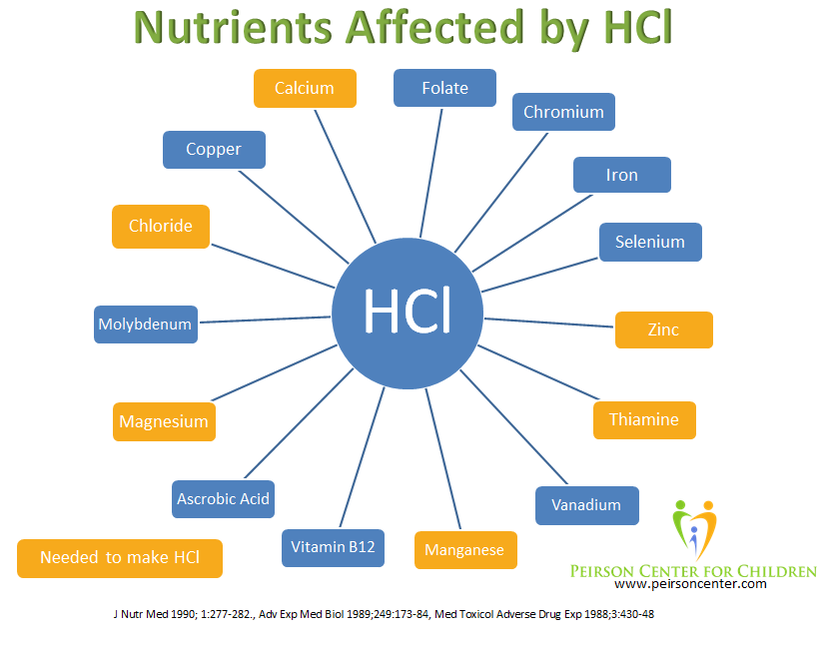

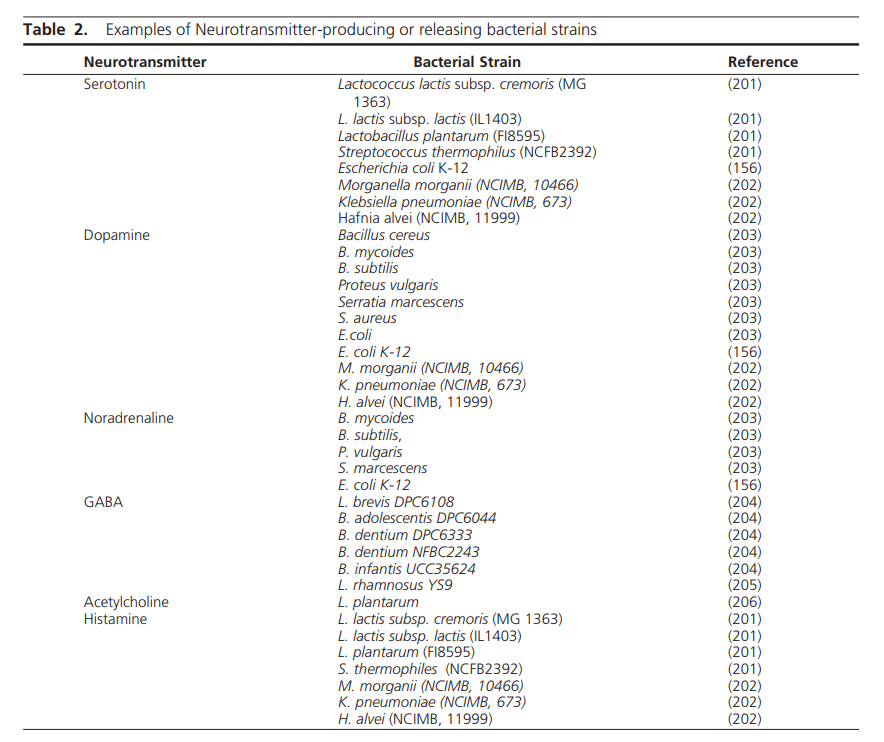

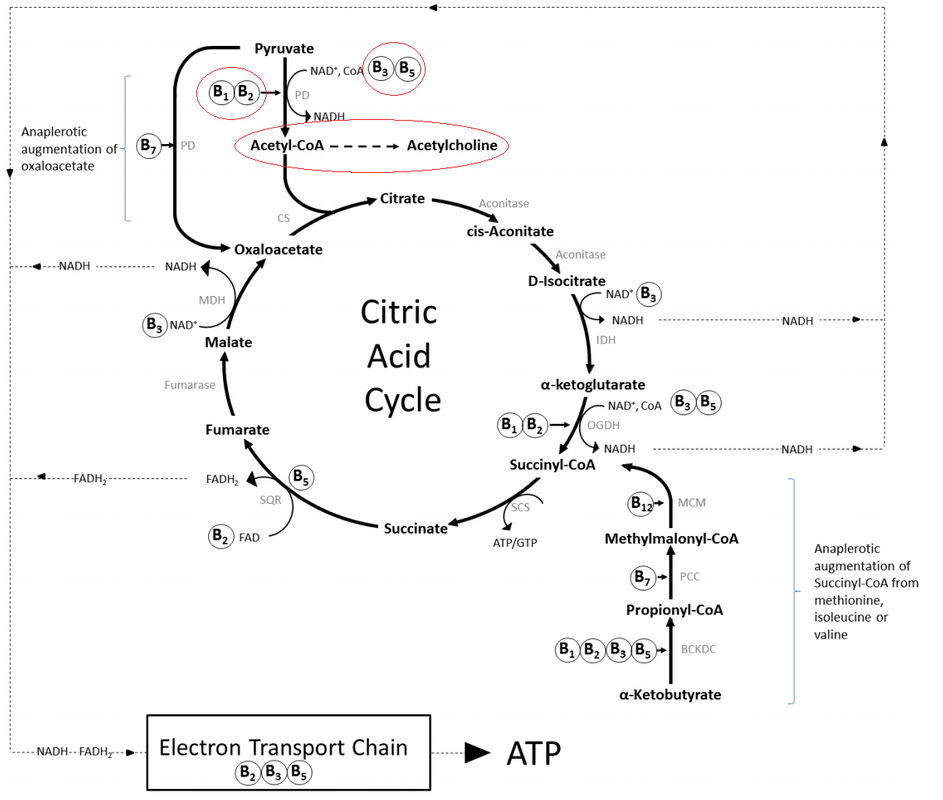

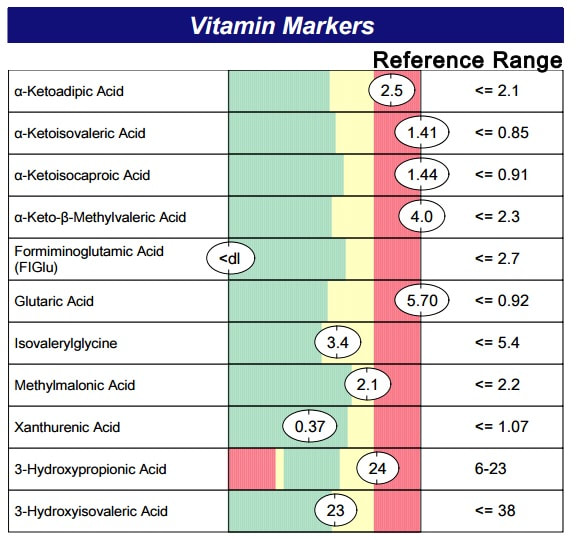

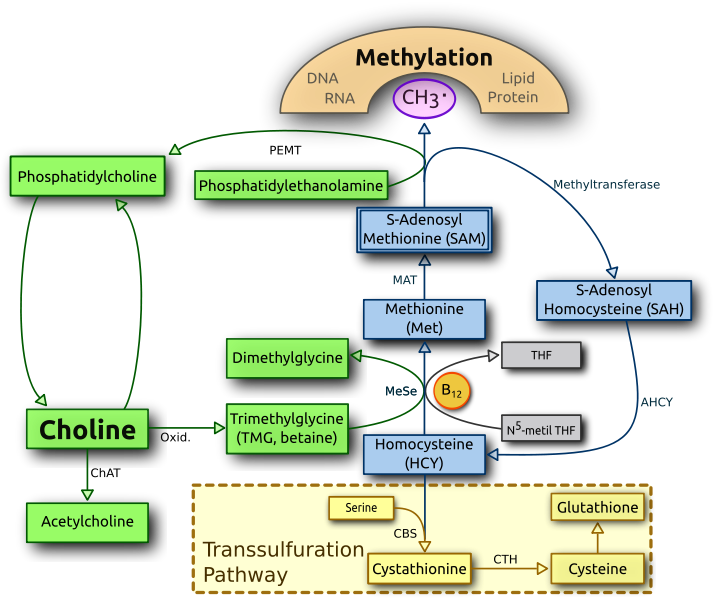

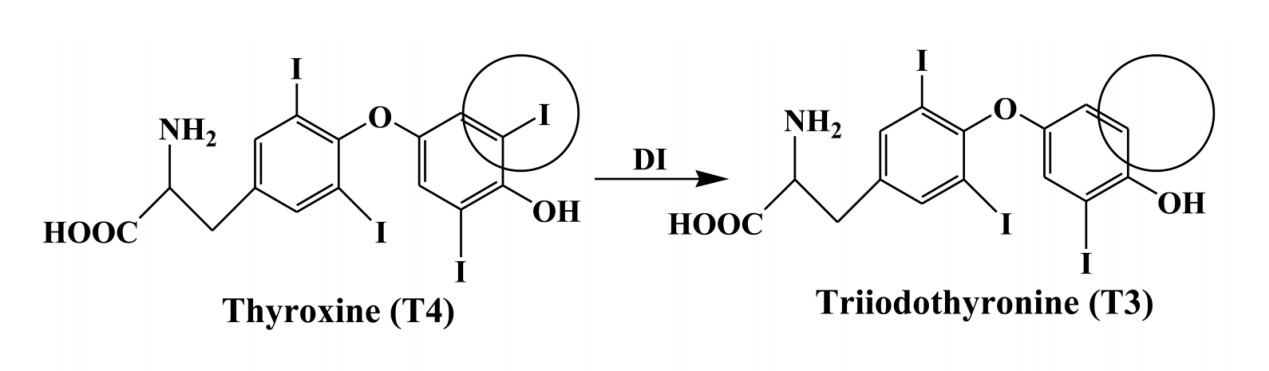

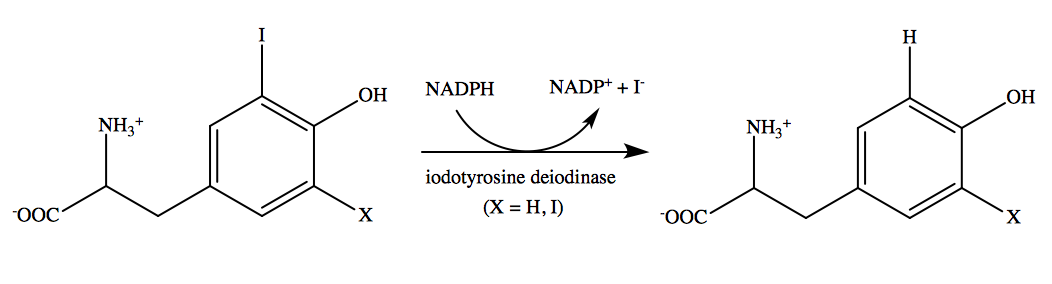

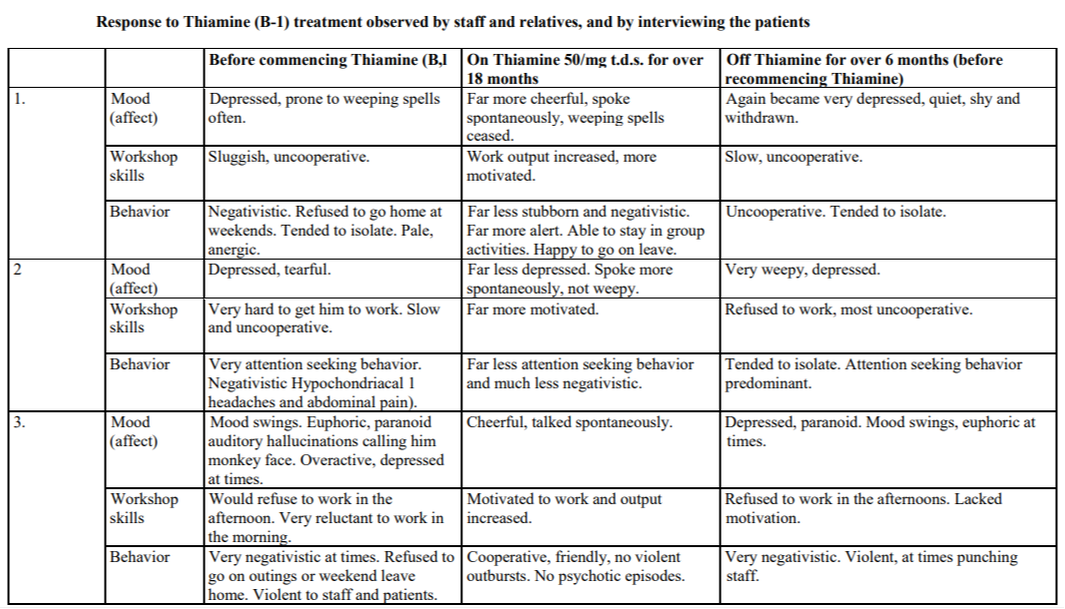

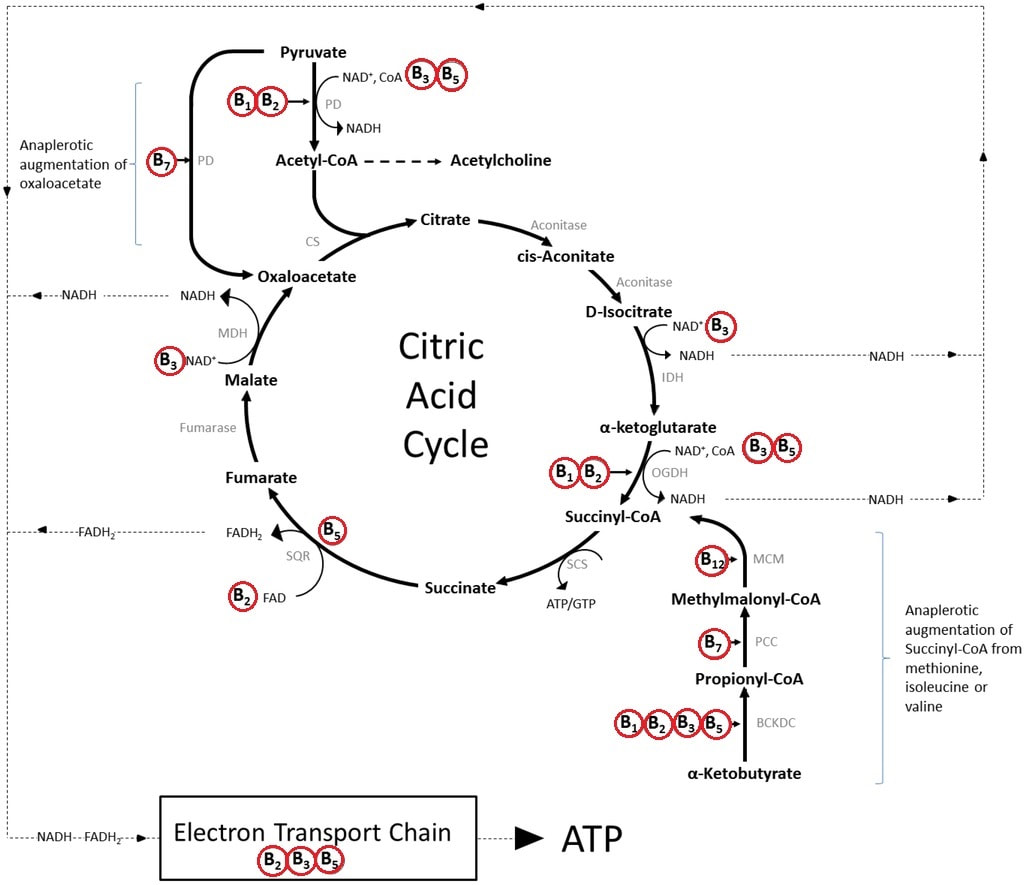

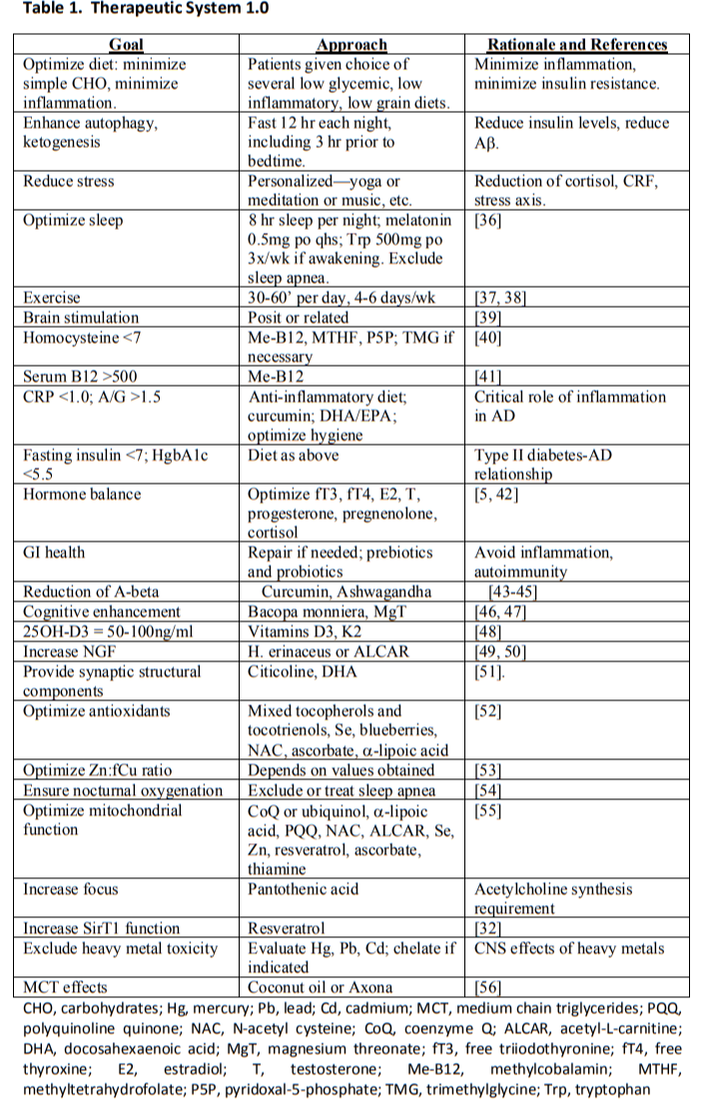

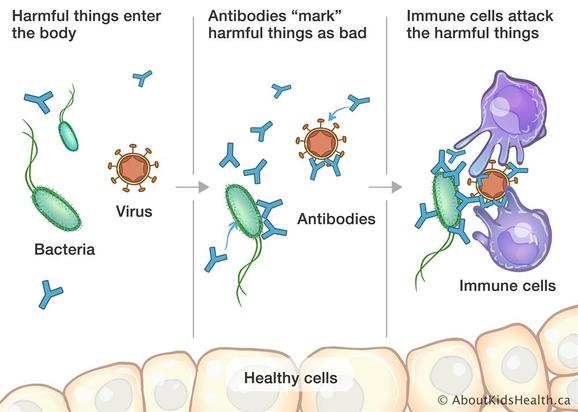

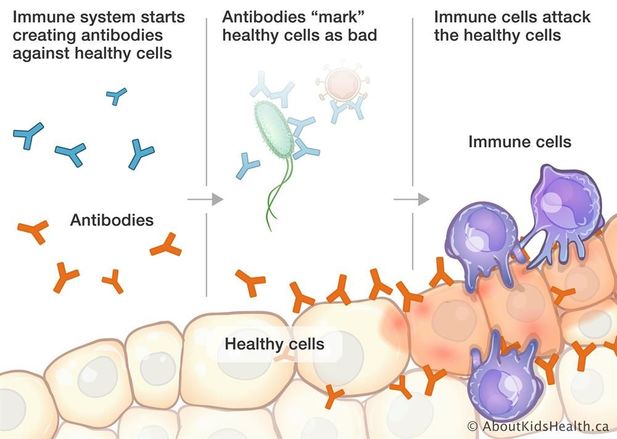

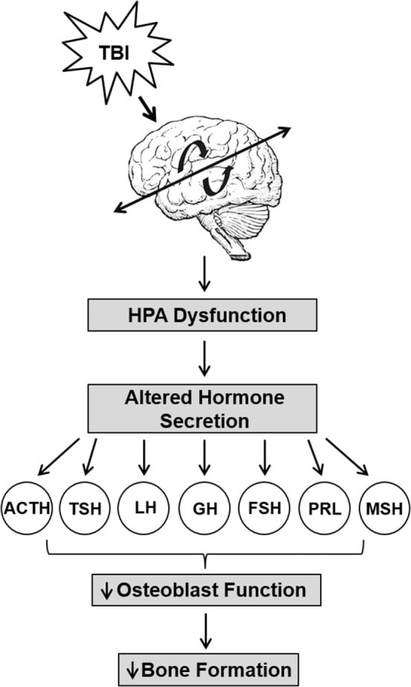

Healthy brain function relies on a variety of biochemical factors including neurotransmitters, neurotrophic factors, neurohormones, antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, glucose, B-vitamins, minerals and phospholipids.

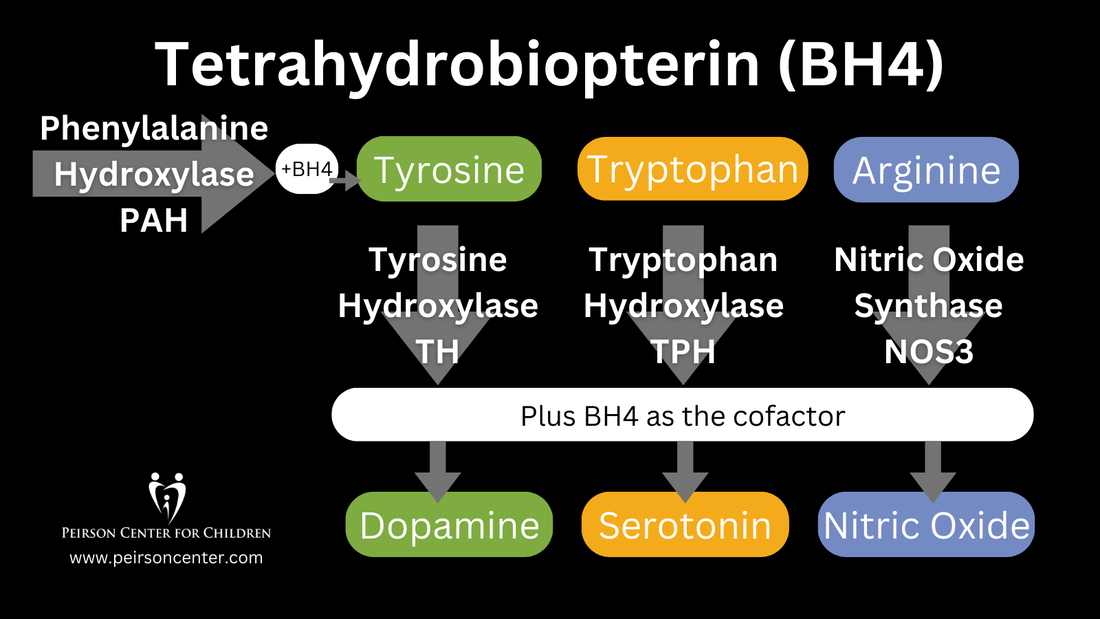

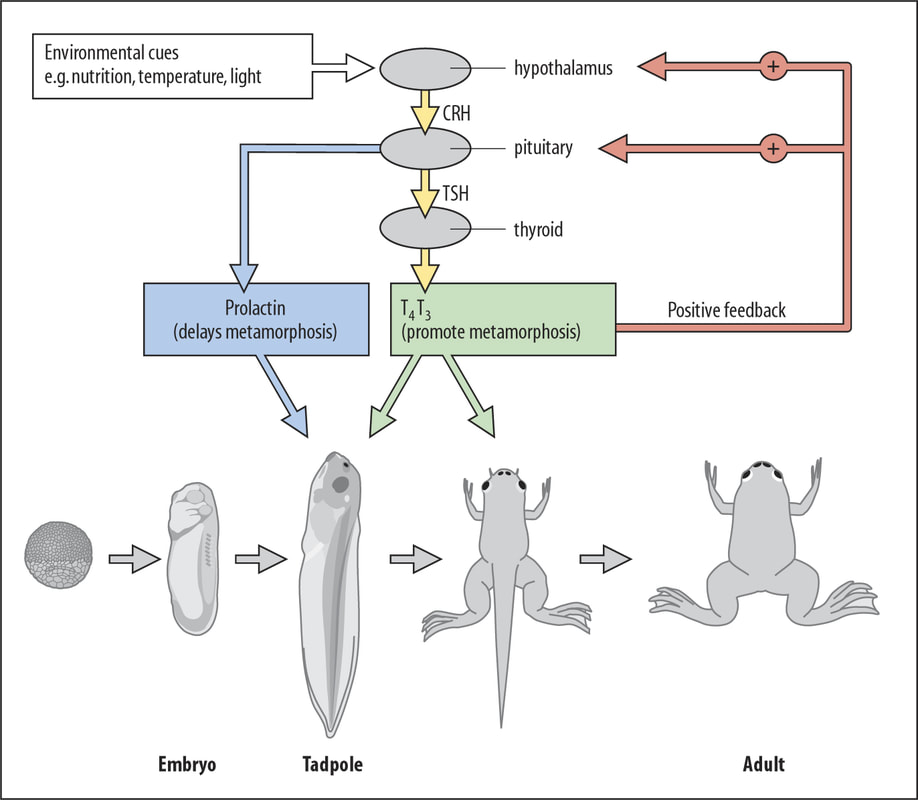

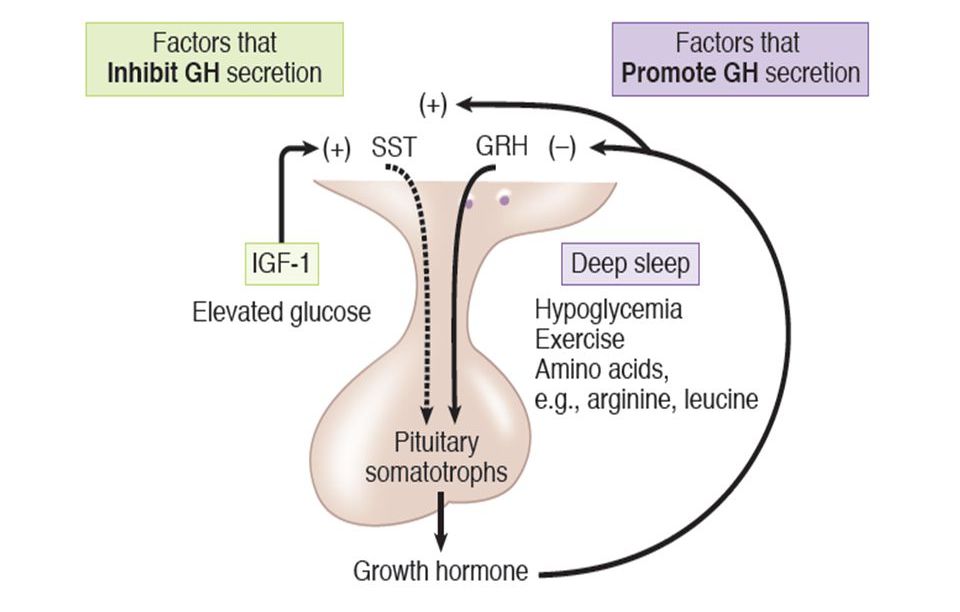

Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is one of many important factors that impact neurotransmitters in the brain and nervous system. It's a vital cofactor in the synthesis of several neurotransmitters and is crucial for multiple metabolic pathways in the body. |

|

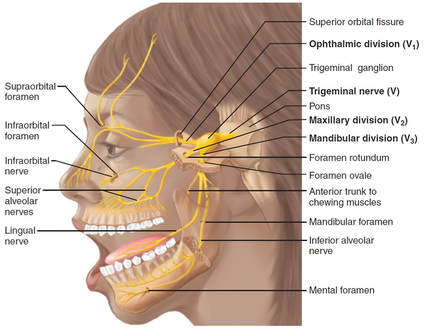

Low levels of BH4 can lead to a range of signs and symptoms, including neurological and psychiatric manifestations. Neurological symptoms may include developmental delay, movement disorders, such as dystonia or tremors, and seizures. Psychiatric symptoms associated with low BH4 levels may include mood disturbances, such as depression or anxiety, as well as cognitive impairments. Low levels of BH4 resulting in low dopamine can even impact speech resulting in ataxia and stutter. Additionally, individuals with low BH4 levels may experience cardiovascular dysfunction due to impaired nitric oxide synthesis, leading to hypertension or vascular complications.

|

|

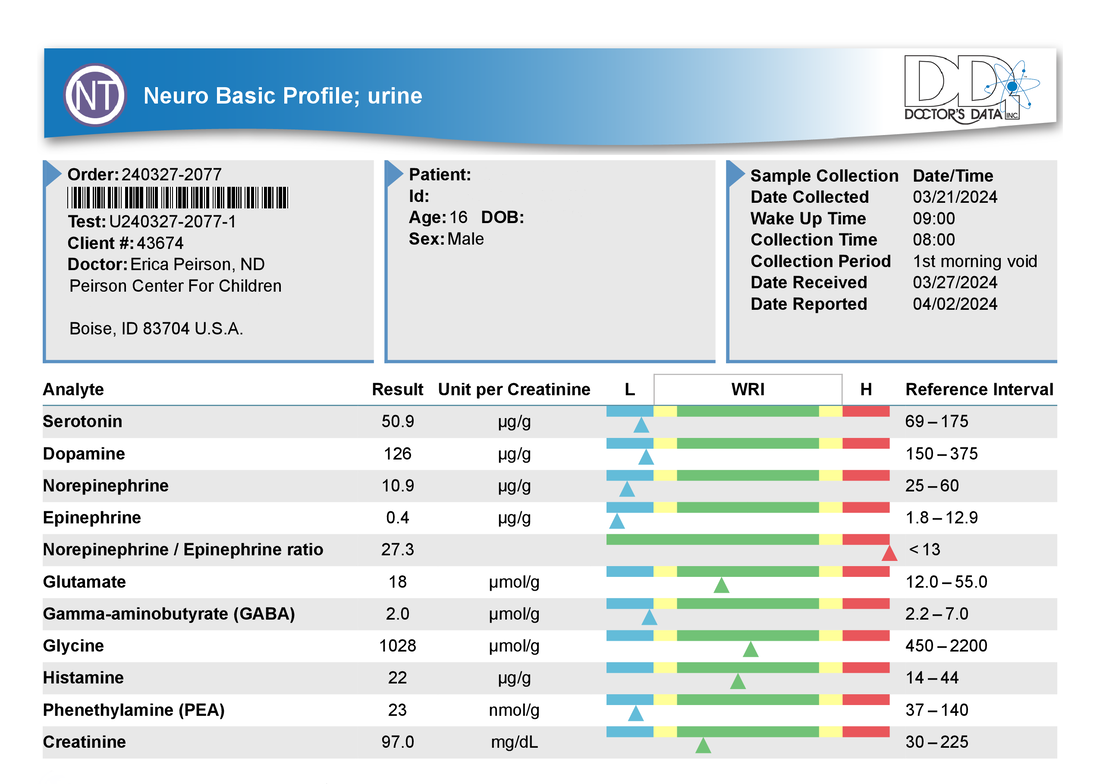

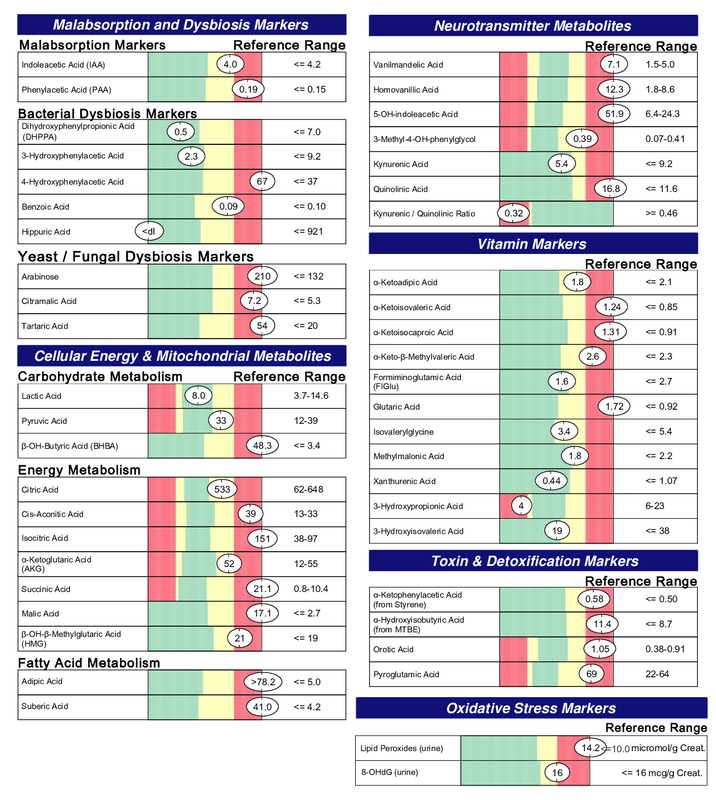

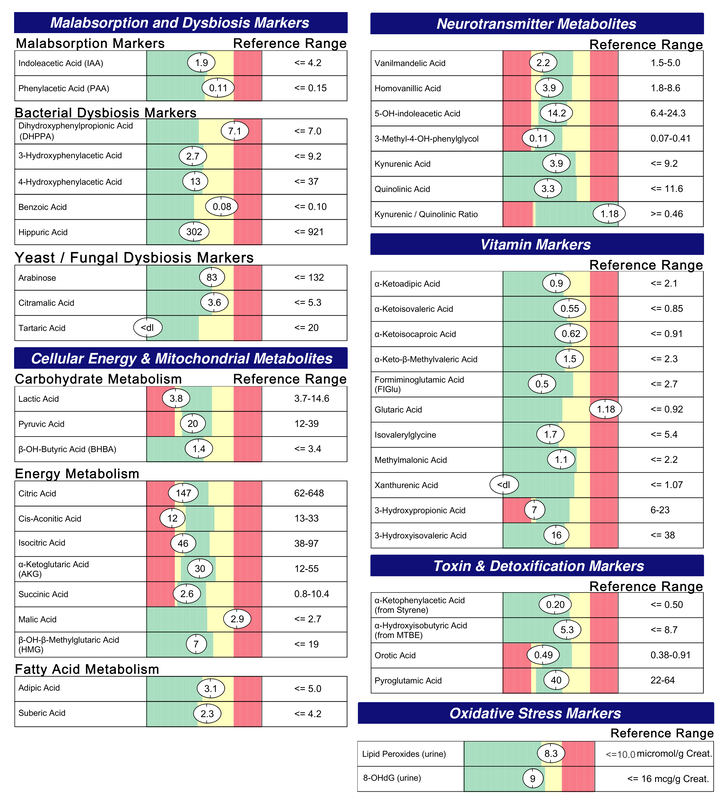

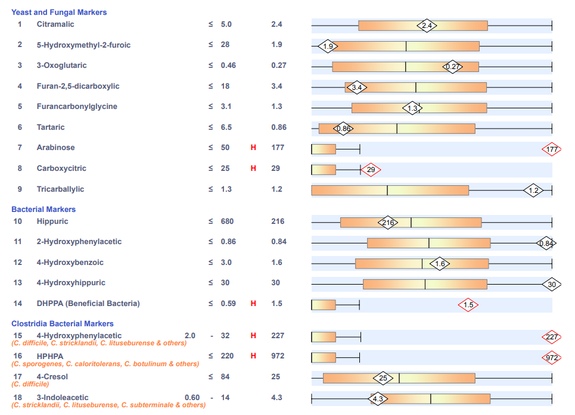

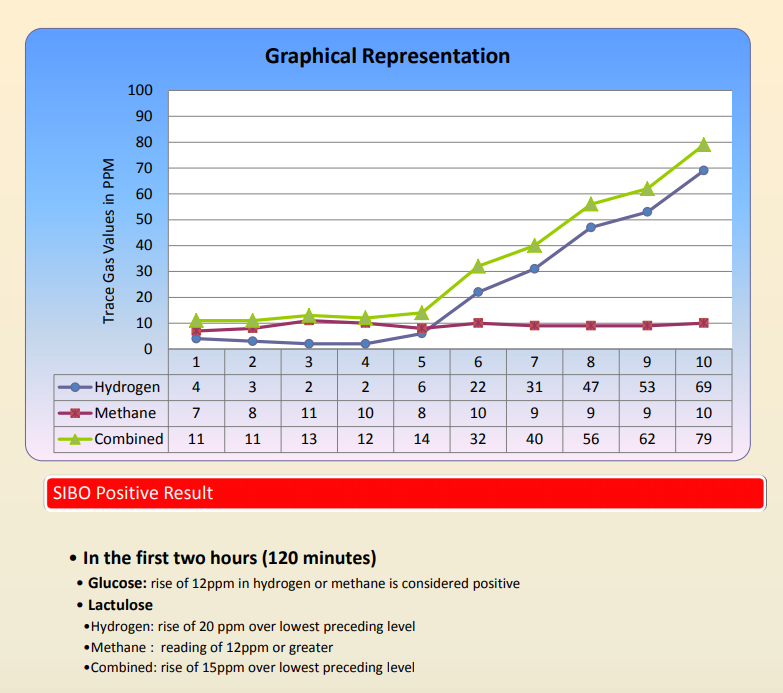

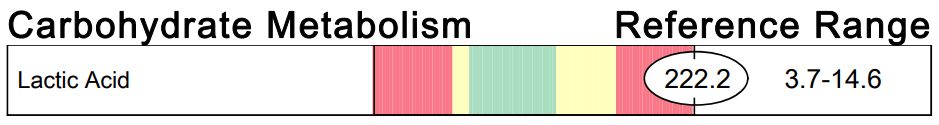

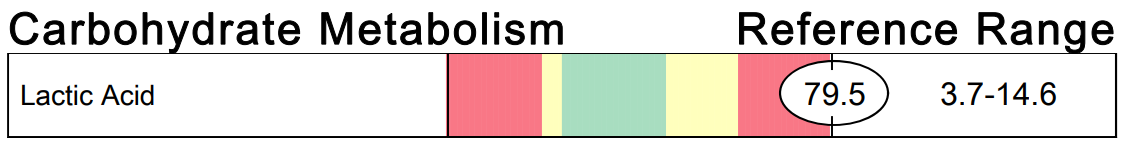

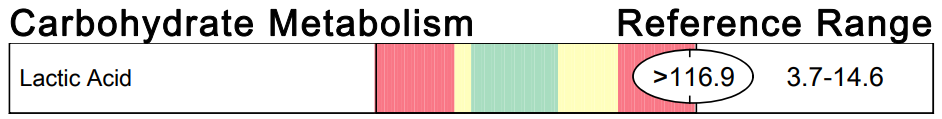

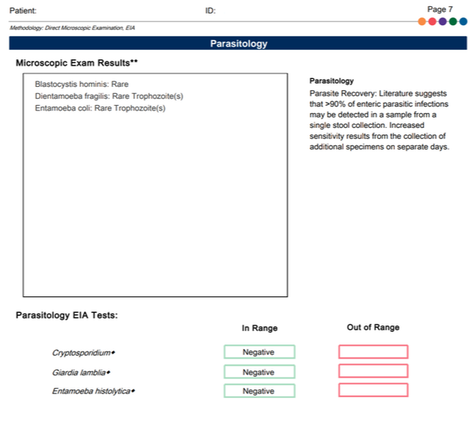

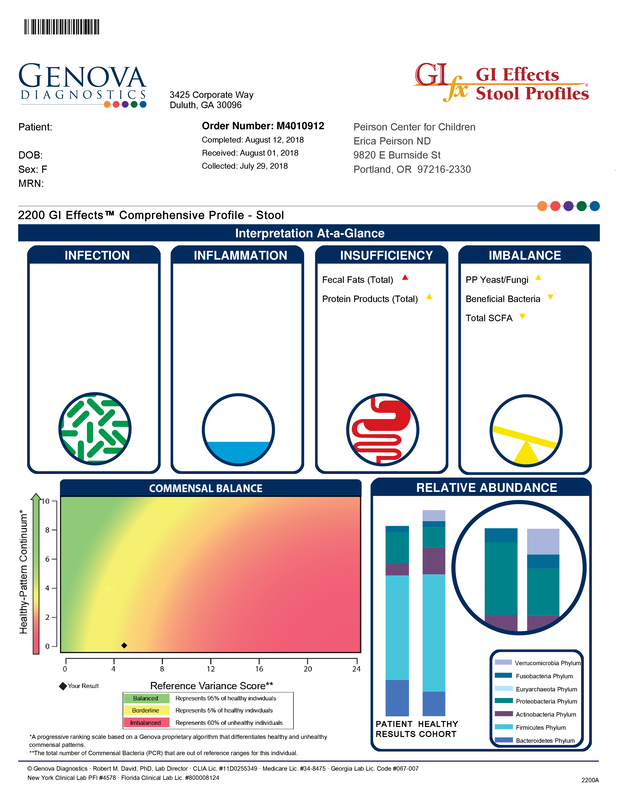

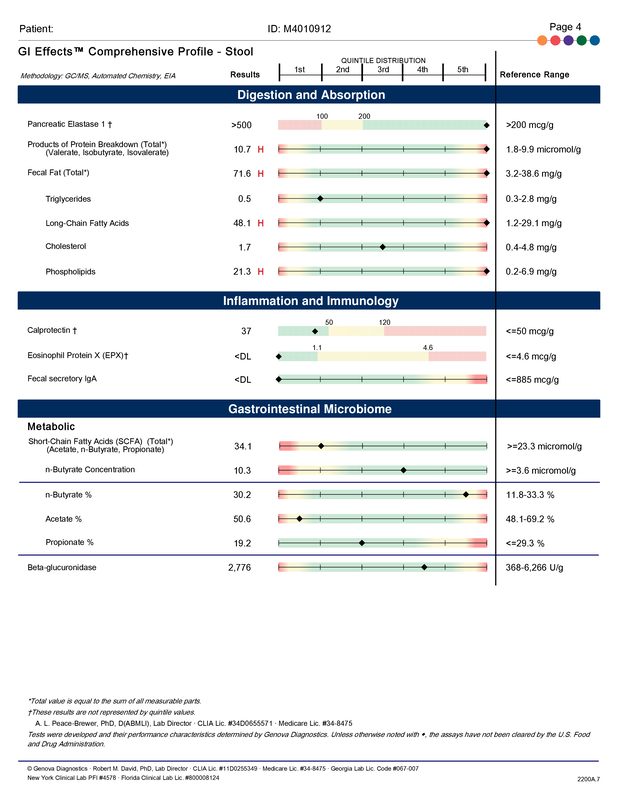

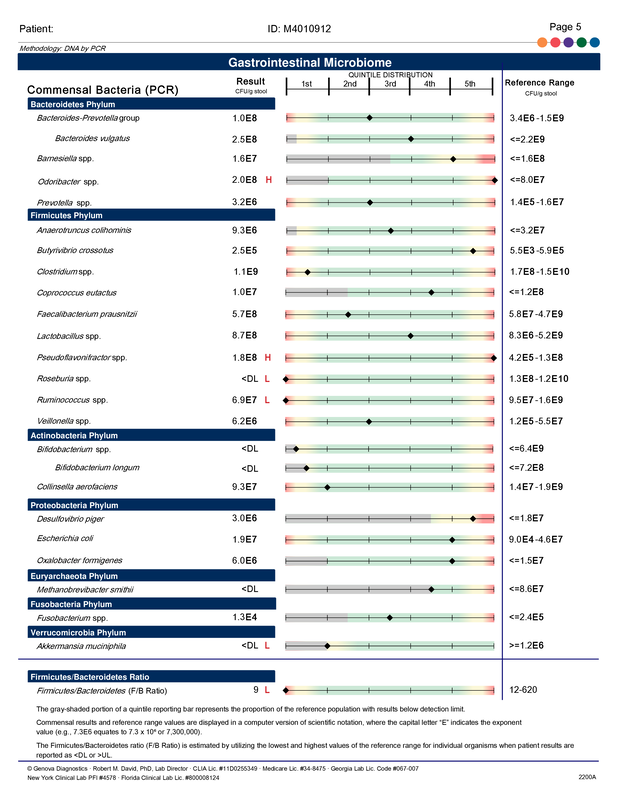

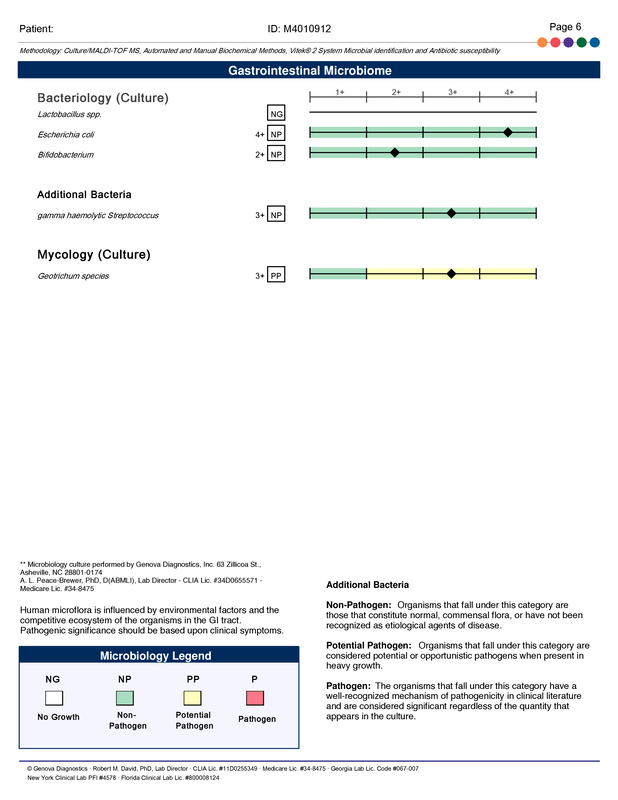

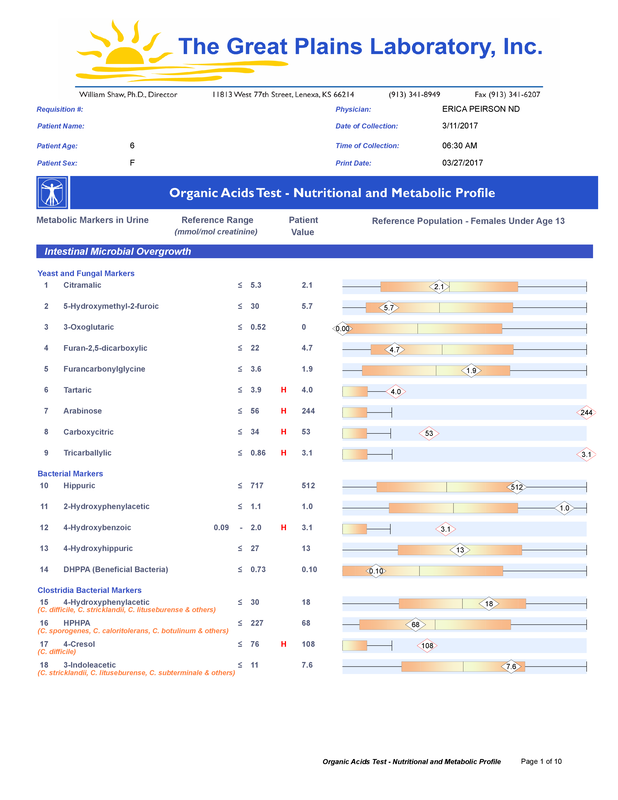

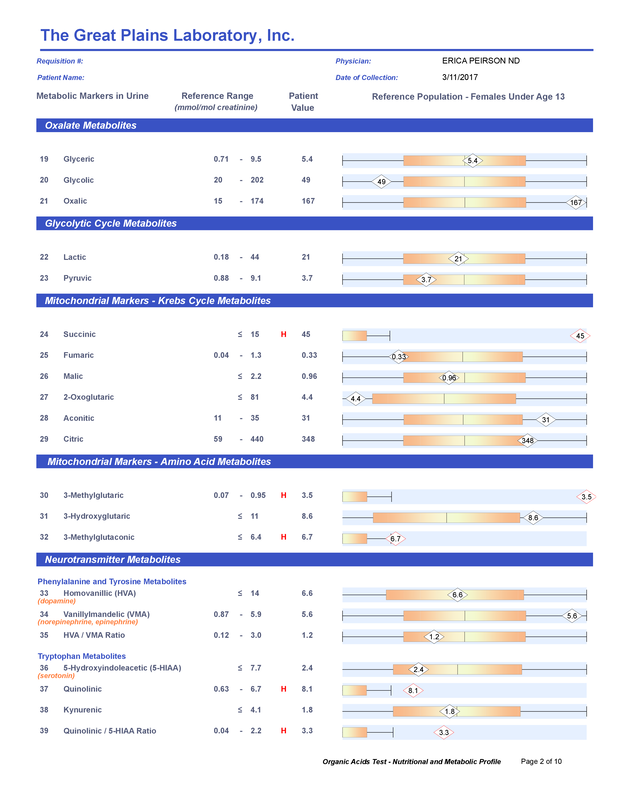

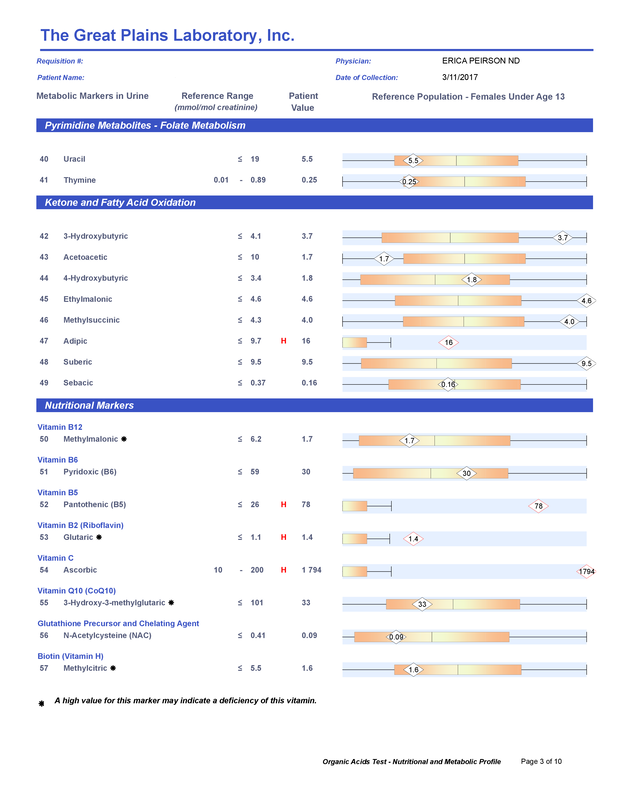

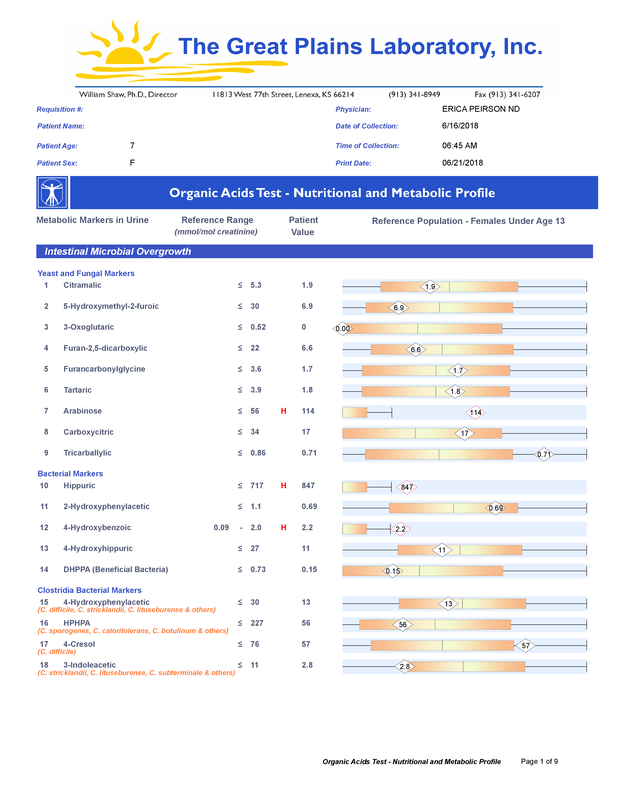

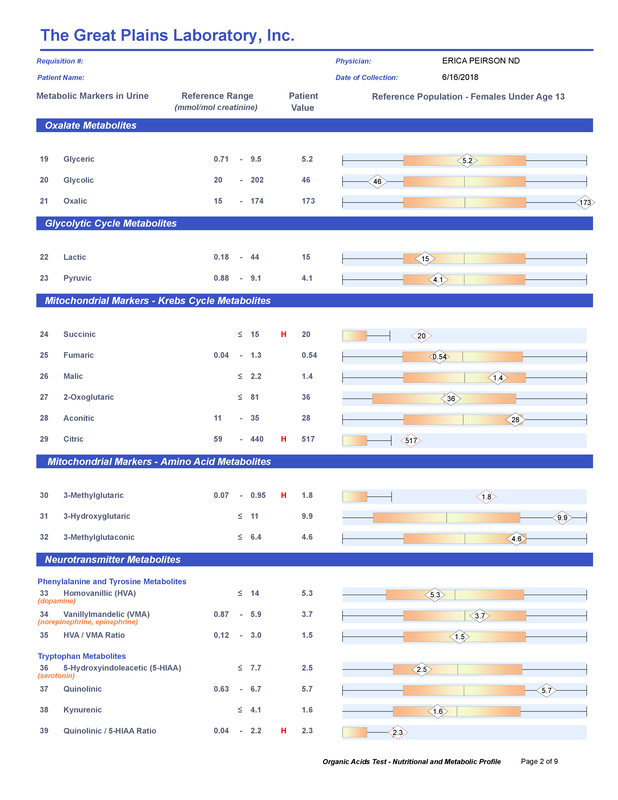

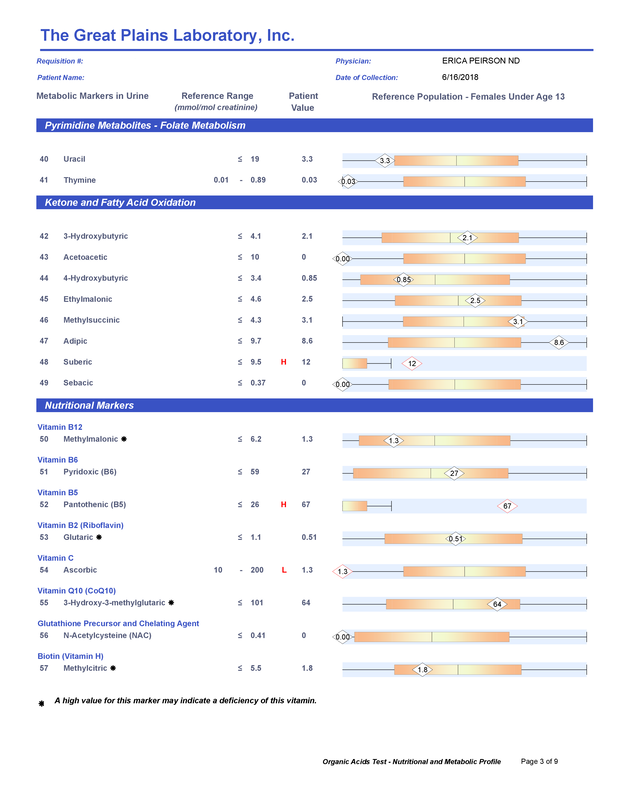

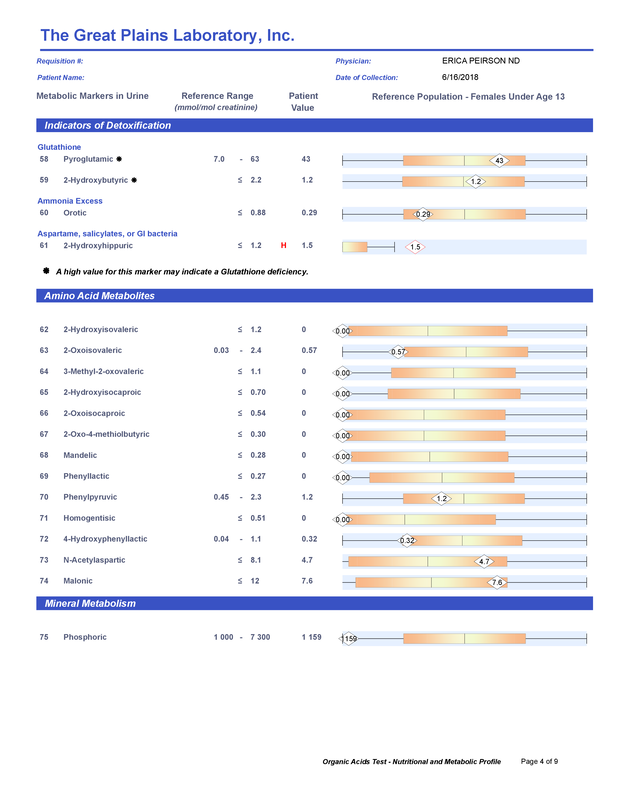

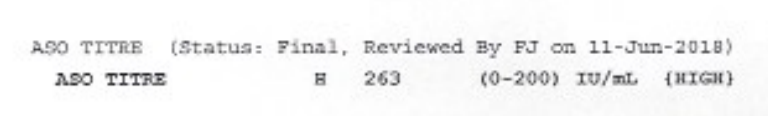

A commercial test for assessing a BH4 level in the body is not commercially available at this time. However, nitric oxide levels can be tested safely and easily in saliva using humanN test strips seen here. As well a urine neurotransmitter test like the NeuroBasic Profile can be done through Doctor's Data that includes dopamine and serotinin levels. A sample report of this test can be seen here from a patient who has a stutter, which has been linked to low dopamine levels. (Alm 2021)

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed